This article has been contributed by author Rhoderick W. J. Jones. His book John Ashburnham: Faithful Servant of King Charles I is out now.

An exhibition of items from the Ashburnham family collection is currently on display at Carisbrooke Castle Museum.

When I was appointed Head Gardener & Grounds Manager of Ashburnham Place in East Sussex, I soon realised that there was much more to this historic estate than its beautiful ‘Capability’ Brown landscape of woodlands, lakes and gardens. In the midst of the Ashburnham family’s 900 year story, there is one particular character who was active in the highest society in the land at the most turbulent period of our constitutional history, with an unwavering loyalty to his friend the King – but who today is rarely mentioned in histories of this tumultuous period.

The quiet rural village of Ashburnham was home from the 11th century to Ashburnham Place and the family of the same name, and remained so until Lady Catherine Ashburnham died in 1953. I began researching the history of the Ashburnham family and, in amongst many generations of ‘John Ashburnham’, came across the John Ashburnham who was born in 1603. The family had been gradually rising in wealth and status across the generations, successfully navigating their way through the ups and downs of history – until John’s father bankrupted the family estate. However, at the age of 19, just two years after his father’s death, John had restored his family’s hope, reputation and standing in society – sufficiently so that, in his early 20’s – and through a family connection with the Duke of Buckingham and under his patronage – John began a career in the Court of King Charles I.

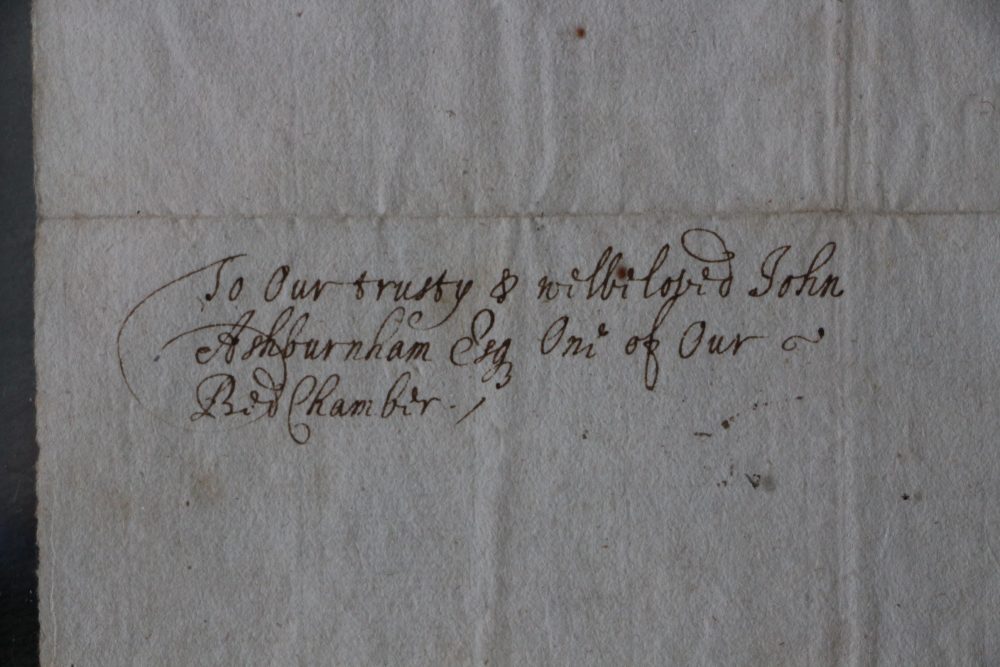

By 1627 John was sufficiently close to the King that he was referred affectionately in the King’s personal letters as “Dear Jack Ashburnham”, and was made Groom of the Bedchamber. He became Member of Parliament for Sussex and, with the onset of the Civil War, was sent to the King’s supporters on numerous occasions to raise money on the King’s behalf. A detailed Accounts Book from the period shows all the monies collected by John for the King’s cause, with the King’s signature approving each page’s records.

Throughout the conflict John was by the King’s side, and when the tide turned and the Parliamentarians took the upper hand, John was one of the key negotiators with Cromwell and Ireton on the King’s behalf. When King Charles felt sure an assassination attempt was becoming inevitable, it was John who was entrusted to organise the King’s escape. Many historians have blamed John for the King’s decision to go to the Isle of Wight, and for his ultimate failure to secure a deal with Parliament. However my research has led me to conclude that the King always had the final word on all decisions taken – and that as a loyal servant John always did what the King asked of him. Charles acknowledged John’s loyalty in a letter he wrote to the Queen, which refers to:

“Jack Ashburnham….the most (and with the greatest injustice) persecuted of all my servants, and merely for his fidelity to me”

I believe that John was a man of honour and integrity prepared to submit his life to what he believed was the omnipotent power and authority of God, whom he believed had appointed King Charles to rule the land.

Following defeat in the Civil War and the King’s execution, many Royalists apportioned blame to John for the failure of the King’s cause. The Parliamentarians saw him as a traitor to their cause, and imprisoned him for many years, imposing heavy fines upon him.

Yet in spite of all this John survived, and at the restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 Charles II reinstated him to his former position of Groom to the Bedchamber where he served for the rest of his life. John also received such financial reward as the Treasury could afford, in recompense for John’s expenditure on the King’s cause. Nevertheless John was a relatively poor man and remained simply ‘Esquire’ (his descendants achieving an Earldom in 1730) – though he was re-elected as Member of Parliament for Sussex.

John’s home at Ashburnham Place, alongside the adjoining parish church, were both destroyed by Parliamentarian action. John started with the rebuilding of the parish church – where monuments to John and other members of his family can still be seen – before later rebuilding his own house. John remained engaged in society life; towards the end of his life Samuel Pepys makes mention of John in his Diary:

“and then to Sir G Carteret’s to dinner and here was also Mr (John) Ashburnham, the great man, who is a pleasant man, and hath seen much of the world, and more of the Court”

John died in 1671. He left behind a wealth of primary sources, including an autobiographical narrative of his actions (later published by his descendant the 3rd Earl of Ashburnham in 1830), as well as personal artefacts belonging to the King which are now on display at Carisbrooke Castle Museum.

Fast forward 300 years, and the culmination of John’s legacy – following the death of Lady Catherine Ashburnham in 1953 – was the establishment of the Ashburnham Christian Trust in the 1960s by Revd. John Bickersteth, grandson of the 5th Earl Ashburnham, which regularly receives up to 20,000 visitors a year.

I hope that my book, and the public display at Carisbrooke Castle Museum, will bring a wider awareness of the extraordinary story of this man and his friendship and devotion to his King and his God, and the legacy this left for the generations that followed.